By Dr Tom McAuley

In this article, Dr Tom McAuley provides some background to his Futurecade exhibit ‘A Mirror it Does Seem‘ and the research on premodern Japanese poetry and poetic criticism that informed it. He also provides context about the poetry, and the society and culture that produced it.

The term ‘premodern Japan’ obviously encompasses many centuries, but the period I’m most interested in runs from about 900-1200 when Japan was largely peaceful and its ruling nobility had settled in the city of Heian-kyō (modern day Kyoto) around the court of the emperor.

This was a time of significant cultural development in Japan, not least in literature and in poetry, in particular, because the writing and appreciation of poetry was an integral part of aristocratic life. Everyone in the nobility wrote poetry—in fact, it’s not going too far to say that you couldn’t be a functioning aristocrat without the ability to compose a verse when needed. There’s not really a modern English equivalent, but it would be like being a member of the upper classes in Jane Austen’s time and being unable to dance—you would be a strange figure of fun and ridicule, and not get invited to any parties.

I digress slightly, but there’s an actual example of such an individual mentioned in the writings of the time: Tachibana no Norimitsu (965-?). Norimitsu was by all accounts quite dashing—a number of sources tell the story of how he was able to kill three robbers in a swordfight (you can read my translation of one of these stories here)—but he is also known to have had a relationship with Sei Shōnagon (ca. 966-1017/1025) a court lady and the author of one of the most famous accounts of court life, Makura no sōshi (‘The Pillow Book’). Sei describes the end of their relationship in her book and portrays Norimitsu as a buffoon as he is unable to respond properly to any of her verses, and even refuses to do so!

Nobles used poetry for both describing the natural world and their feelings about it, and also their emotions in response to life events like births, deaths, travelling and, of course, falling in love and out of it. An individual was not free to compose about anything any way he or she liked, however—there were rules about what topics were suitable for poetic composition, about which emotions should be expressed depending upon the topic, and what words could and could not be used in poetry. There was also only one form for acceptable poetry: the waka, a short verse in a pattern of 5-7-5-7-7 syllables.

The topic of our project, the moon and its reflection in water, was associated with autumn—the best night of the year for viewing it was believed to be the 15th day of the Eighth lunar month (around mid-September)—just when the Festival of the Mind is taking place. At this time of year, aristocrats would gather together, either at their estates, or at places where it was known the moon looked particularly beautiful, and enjoy the sight in each other’s company, composing poems as they did so. One just one such occasion:

When he had first gone to the residence of the former Regent and Rokujō Minister, and people were composing on the conception of long clear pond waters.

今年だに鏡と見ゆる池水の千世経てすまむ影ぞゆかしき

| kotoshi dani kagami to miyuru ikemizu no chiyo hete sumamu kage zo yukashiki | Especially this year A mirror it does seem: This pond water – Clear through the passage of a thousand ages, How I long for its light! |

Fujiwara no Norinaga (ca. 993-?)

藤原範永

(Translated by Thomas McAuley ©)

Poems were exchanged between friends and lovers, sent to superiors, were written for recitation at functions held at court and the mansions of the senior nobility, and also to accompany artworks on the screens which were used for decorating aristocratic dwellings. So, there has been a long association between waka and artwork, making this project a continuation of this centuries old relationship.

Waka were also collected into anthologies so they could be passed down to individuals’ descendants as a social and cultural inheritance. Of course, in order to decide which poems were worth preserving, critical poetic standards had to be developed, and the formal criticism of poetry became increasingly important from the mid-eleventh century. One of the most important venues in which poetry was criticised was the poetry competition (uta’awase), where poets would present their work and have it criticised and judged by experts (for more information on uta’awase, see here). Possibly the single most famous such contest, and certainly the largest judged by a single person is Roppyakuban uta’awase (‘Poetry Contest in Six Hundred Rounds’; 1193-94), my translation and commentary of which has recently been published (if you want to hear me talk about poetry contests, Roppyakuban uta’awase and the translation, watch the video, below:

One of the one hundred topics covered in this contest was ‘The View over Hirosawa Pond’ (hirosawa no ike no chōbō). This view was, of course, of the moon. The pond is still there in the north-west of Kyoto, and you can see some pictures of it (in spring, not autumn) here.

Two of the poems composed on this topic for the contest were:

Left (Tie)

澄み来ける跡は光に残れども月こそ古りね広沢の池

| sumikikeru ato wa hikari ni nokoredomo tsuki koso furine hirosawa no ike | Limpid Traces of light Remain, and yet The moon shows no sign of age Above Hirosawa Pond. |

Fujiwara no Sada’ie (1162-1241)

藤原定家

Right

隈もなく月澄む夜半は広沢の池は空にぞ一つなりける

| kuma mo naku tsuki sumu yowa wa hirosawa no ike wa sora ni zo hitotsu narikeru | Completely full The moon is clear at midnight: Hirosawa Pond and the heavens Have become as one. |

Fujiwara no Tsune’ie (1149-1209)

藤原経家

The Right state: we wonder about the appropriateness of ‘light remain’ (hikari ni nokoru) followed by ‘the moon shows no sign of age’ (tsuki koso furine)? These expressions are too similar in meaning to be used so close together. The poem also lacks any conception of a person doing the ‘Viewing’. The Gentlemen of the Left state: the Right’s poem has no faults.

Shunzei’s judgement: on the Left’s poem, I do not strongly feel that the expressions ‘traces of light’ (ato wa hikari ni) and ‘the moon shows no sign of age’ (tsuki koso furine) are particularly bad, but the gentlemen of the Right have identified them both as faults. As for the Right’s poem, I do not feel that there is much sense of a person viewing the scene in expressions such as, ‘pond and the heavens’ (ike wa sora ni zo), and the frequency of wa in tsuki sumu yowa wa, and ike wa, means the poem’s overall impression is poor; it is truly unfortunate that I cannot declare the Left, which lacks a sense of a View, the winner.

(McAuley, Thomas E. (2020) The Poetry Contest in Six Hundred Rounds: A Translation and Commentary. Leiden: Brill: pp.392-93)

Whether or not you agree with Shunzei and the participants’ opinion of the poems, it is these which inspired Roanna and Alison to collaborate in creating the artwork for this exhibition, which they discuss below.

Roanna Wells

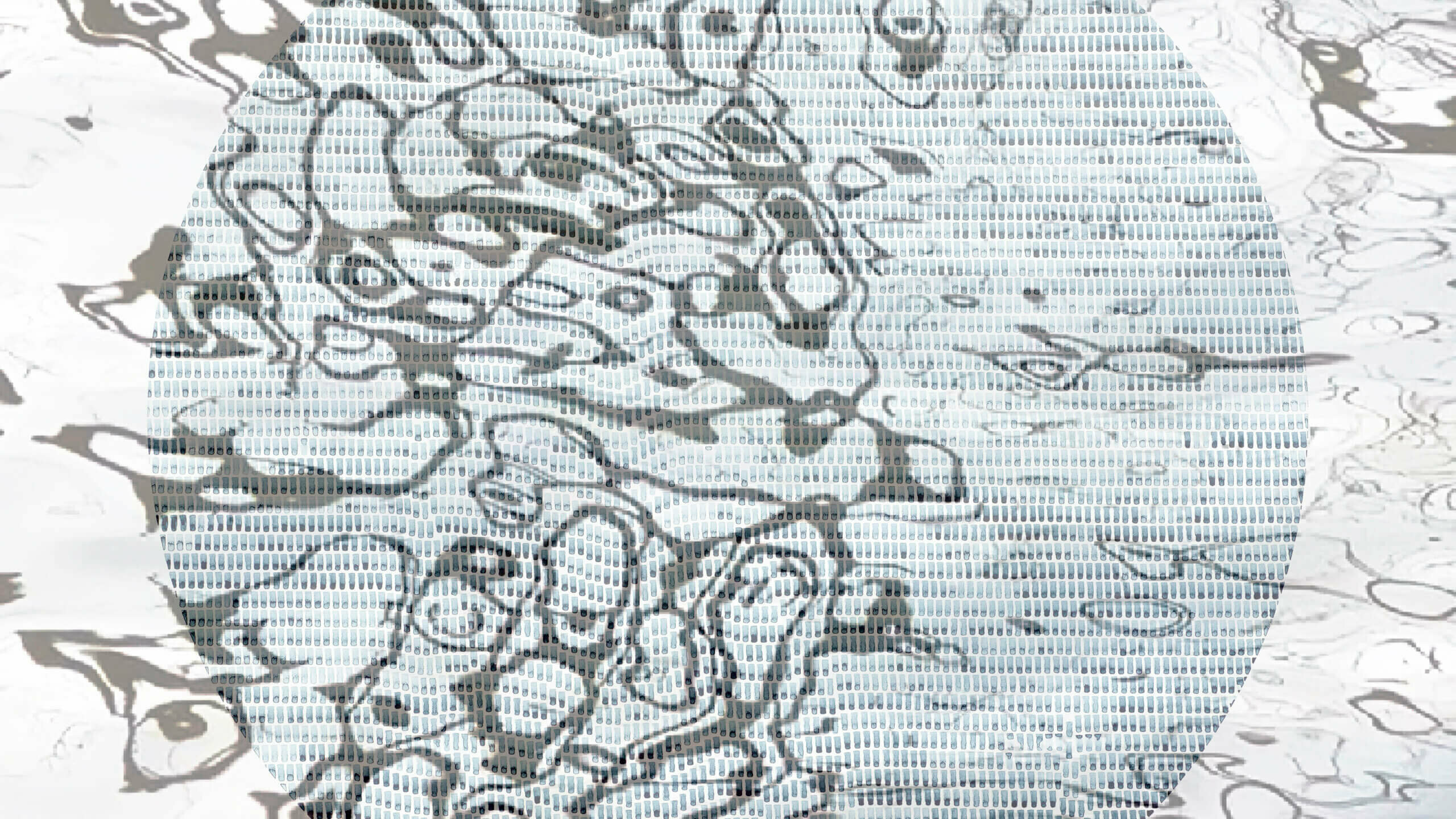

Roanna Wells’ work involves a meditative process of repetitive mark making and often conveys a quiet but deep introspection expressed through simplicity of colour and pattern. The series created for this project gives a visual sense of the moon being reflected in water, but also touches on the idea of personal reflection and themes of self-exploration, growth and change.

Alison Churchill

Alison Churchill makes work in response to the mesmerising and constantly changing light patterns and reflections on Sheffield’s ponds, millraces and rivers. In this project she floods Wells’ meditative moon paintings with water patterns, and suspends the poems in translucent and reflective surfaces.

Gazing at light effects on water is a timeless activity, invoking inner reflection. This exhibit aims to create a contemplative space dissolving historical and cultural boundaries, inviting viewers to connect with the hearts and minds of the Waka poets — and possibly inspiring them to write poems of their own.

Tom McAuley

If you want to find out more about Tom’s work on waka, check out his Waka Poetry website where you’ll find over 6,000 poems translated into English. You can also receive translations via email if you sign up to his mailing list, follow him on Twitter (@wakapoet) or on Instagram (@utadokoro),