The project

Care is in crisis. Austerity and staff shortages have placed increased burden on the care system. COVID-19 has placed further pressure on individuals, families and the care workforce.

The exhibition is a provocation to think about how we can support each other in Sheffield and as a society.

Drawing on recent research from Dr Matthew Lariviere, Centre for International Research on Care, Labour & Equalities (CIRCLE), on care; Akeem Balogun, Kate Morgan and Rob Richardson produced an audio-visual collection of ‘carescapes’, immersive stories and illustrations to evoke potential near and distant futures of a society focused on care and empathy.

The stories

Comprehensive and Assistive Robotic Enhancer

How many years?

The illustrations

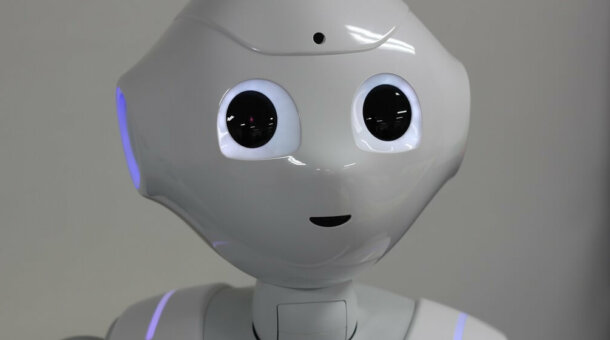

Although our culture often portrays robots as harbingers of doom, like The Terminator, many people in health and care believe robots offer a lot of potential for transforming the lives of individuals and our care systems.

In the future, robots could play a role in supporting people with everyday activities in their homes and communities.

Does it matter what our robots look like? What do you think about the robot depicted in this image? Would you want it to provide care for you or a loved one?

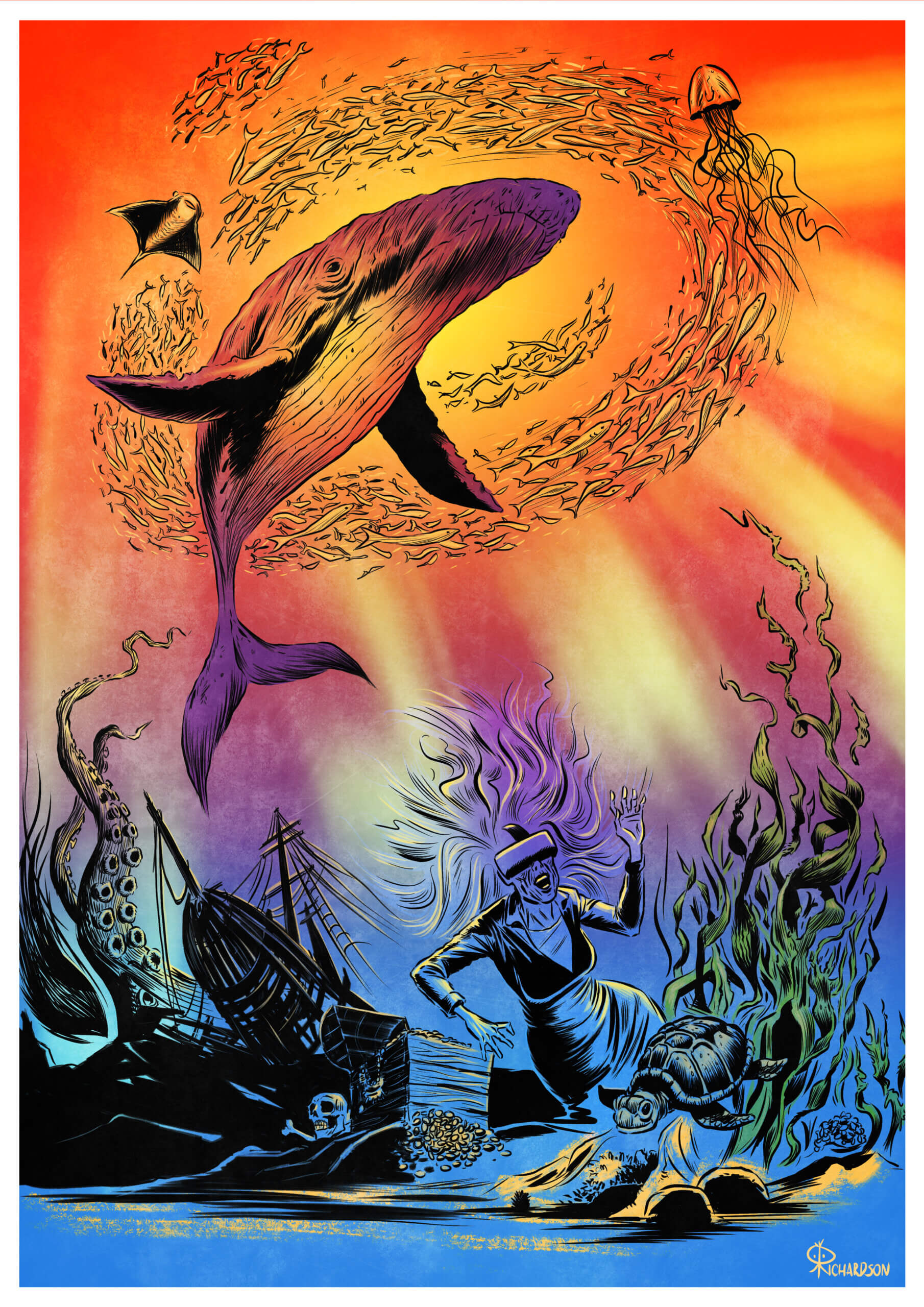

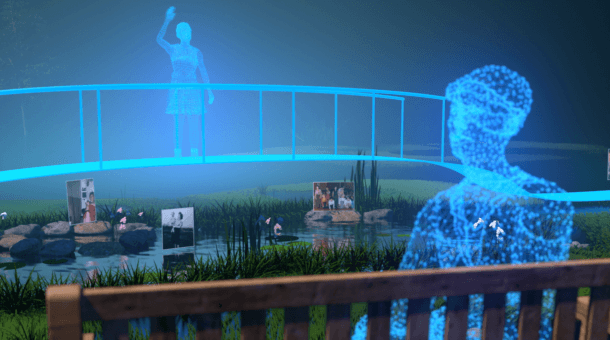

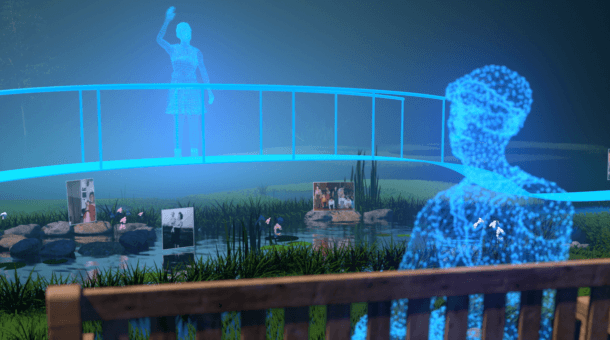

Augmented and virtual reality allow for technology to shift how we perceive and interact with our environments. As we become frailer due to age or disability, we may no longer be able to participate in leisure and recreational activities we once enjoyed. If we once enjoyed scuba diving and exploring reefs, then virtual reality may provide a way to experience a

simulation of that experience.

Could augmented and virtual reality provide an immersive and positive experience for people as they become less mobile? What kind of experiences would you want to maintain through this technology?

Social policy focuses on the idea of ‘ageing in place’, the goal to let people live in their own homes and communities for as long as possible with increased care and support. However, homes and communities can also be locations of neglect and abuse.

How can we make homely living spaces within an unwelcoming environment?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many of us have been required to keep physically distant from our families and friends. Many people have relied on digital technology to maintain contact during this period. As physical distancing may remain in place for the foreseeable future, this raises fresh questions about how, and to what extent, virtual interactions can sustain socialising with loved ones when kept physically apart.

How important is virtual interaction when socialising is limited? How can we ensure virtual interactions do not exclude the most vulnerable in society?

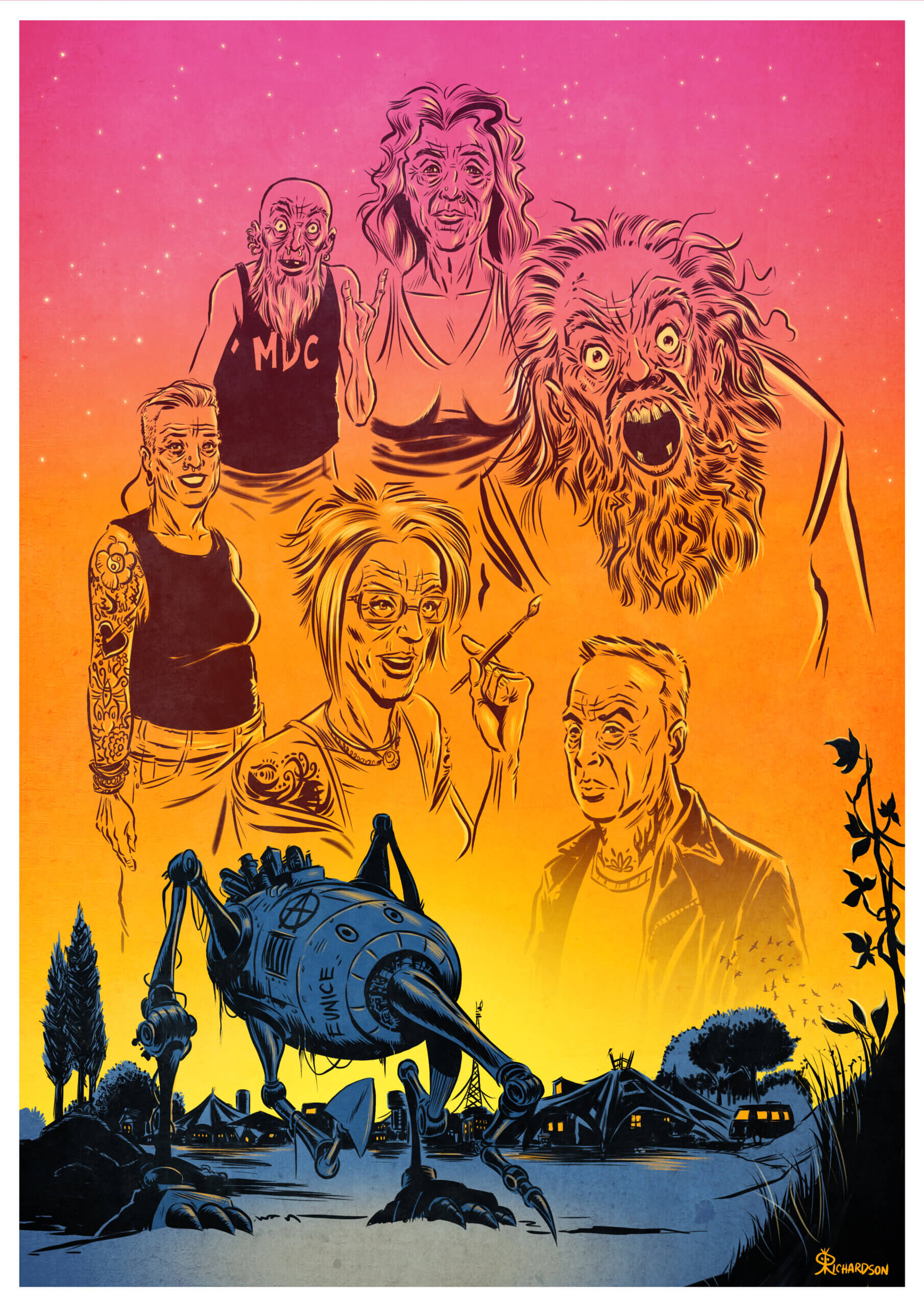

With the current lack of appropriate housing stock adapted for people living with disabilities, we need to think about what kind of spaces and communities we might inhabit in later life. Specialised retirement communities have developed to support people with dementia, like de Hogeweyk in the Netherlands. However, beyond their individual illness and support needs, there is nothing that unites people.

What if we created retirement communities that embraced shared interests and lifestyle choices, like rock musicians or sport enthusiasts?

Digital technology, like Amazon’s Alexa and smart phones, are increasingly common in our everyday lives.

In the not too distant future, digital technology may have a greater role to play in care and support for people at home. They may be robotic ‘helping hands’ or pets to provide assistance in the kitchen or emotional assistance.

Family carers and care workers may also use technology to hold regular virtual meetings with a family member or client to check their vitals and wellbeing.

Such technology may help individuals feel socially connected with their family and communities whilst continuing to live in their own homes for as long as possible.

Would you want robots to feature in your future home? How would you want technology to fit in your life?

Many digital health and care technologies currently rely on phone lines to connect people with care professionals.

In the near future, digital technology may provide alternative means for people to connect with each other. Two-way cameras can allow people to maintain contact despite vast distances.

Care professionals could also use digital technology to monitor vital statistics, such as blood glucose levels and blood pressure, to identify new illnesses or changes in a person’s health, requiring immediate intervention.

Would you want to be monitored in this way? What do you see as the challenges and opportunities for this novel approach?

Our current social care system currently focuses on delivering services arranged by task and time. In other words, care workers often have fifteen or thirty minutes to visit a person’s home to ensure they eat, take medication and other routine tasks.

This model of care does not always centre on what matters most to people. With social isolation and loneliness experienced throughout a person’s lifetime, people may prefer to have time for conversations and social interaction than help with chores at home.

With technology in place to monitor people remotely, families and carers can spend more time during their visit to sit and socialise.

What kind of support would you want if you felt lonely or vulnerable? How would you want to balance this with other social activities?

In the Netherlands, they developed a village-like environment for people with dementia to inhabit called de Hogeweyk. This environment provides access to local shops, hair dressers and other services like any other village. The exceptional quality of de Hogeweyk is that each shop worker and hair dresser is also a care professional. This means people with dementia can maintain the semblance of a normal life while ensuring their safety. Conversely, this model excludes people with dementia from engaging with the rest of society.

What would happen if we recreated a town separate from ‘real’ life? Would it be a space for the elderly to move through life at their own pace or isolate them further? Could life slow down for us all? Could town planning be tailored for us all moving into older age?

Health and social care has seen an increased emphasis on supporting people in their own homes. Since the 1980s, social policy has supported people to receive care in the community. More recently, GPs and other care providers have pushed social prescribing to achieve this goal. However, such support requires navigating multiple complex systems. People with long-term conditions may require specialist support across all public services from health and social care to housing and transportation.

Some local authorities and NHS Trusts have experimented with a ‘care navigator’ role to help individuals navigate within and across public systems to ensure they receive all services that can help support them. In Somerset, the Frome Model of Enhanced Primary Care has health navigators to help patients improve their health and care outcomes.

What other roles could we have to support individuals and families to receive they support they need? What services would you want to ensure you could access?

The team

- For more information about Dr Matthew Lariviere’s work with CIRCLE, visit his staff page or follow him on Twitter @MattLariv

- To read more of Akeem Balogun’s work, visit writtengallery.com or follow him on Twitter @AkeemWrites

- To see more of Rob Richardson’s illustrations, visit his Facebook page or follow him on Instagram

- To see more of Kate Morgan’s artwork, visit illustratorkate.co.uk or follow her on Instagram